The weekend before last, I broke a trip down to London for a week’s research by stopping to visit a friend in Olney, Buckinghamshire.

Amid country walks and good food, it actually turned out to be something of a Romanticist tourist trail (suggestions for alternative terms for such activity that avoid confusion with visitors to Roman sites welcome).

Olney was sometime home to the poet William Cowper (1731-1800). Less well-known now than some of his contemporaries, he was very successful in his lifetime, and had sufficient following to ensure that many of his possessions were preserved by his admirers when he died, so that the Cowper and Newton Museum in Cowper’s house in the town has a remarkable collection of his effects (having visited a good number of literary houses over the years, I can’t recall encountering such an extensive collection of items actually belonging to the writer in question).

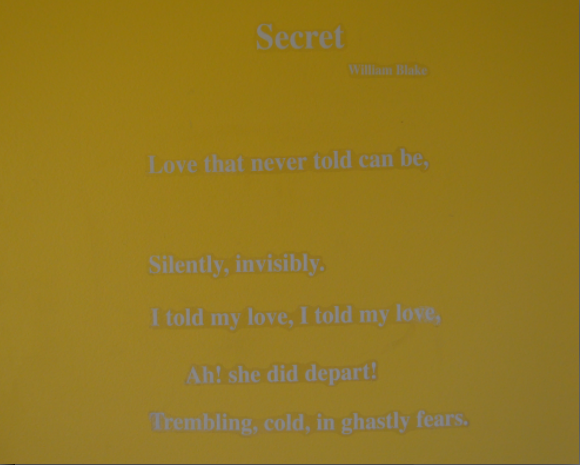

There were even some unexpected Blakean connections. The museum was founded in 1900, largely thanks to Thomas Wright, local school-master and author, whose passions aside from Olney’s heritage included Blake – he even served as Honorary Secretary of the William Blake Society (a precursor to, rather than continuous with, the present Blake Society) for many years.

I knew that Blake had produced some engravings for William Hayley’s Life and Posthumous Writings of Cowper (1803), but I did not expect to find Blake’s original portrait miniature of Cowper in the museum. And this was actually one of two Blake miniatures in the collection, with another of Revd. John Johnson, Cowper’s second cousin and guardian, who visited Felpham in connection with Hayley’s Life and sat for Blake in January 1802. Two more updates have been duly made in my copy of Butlin’s catalogue raisonnée of Blake’s paintings and drawings.

These portrait miniatures are two of a handful of such works by Blake, which have a curious status within his oeuvre. The Cowper portrait was actually a study for Blake’s engraving of the poet for Hayley’s Life, after a portrait by George Romney, but usually such works were painted from life as keepsakes for loved ones (an equivalent these days is having a photo of loved ones as wallpaper on a mobile phone). Portraiture was not the sort of work that Blake relished; he complained that William Hayley gave him too much of such work, as the patron had for Romney. For Blake, such work was mundane, merely representing the superficial appearance of things.

On a side note, one important thing such works do show us is that Blake could do straightforward representation if he wanted to. So when we see figures with elongated limbs or contorted poses that commonly appear in the sorts of pictures that I work on, it’s not because Blake was a clumsy draughtsman: he broke the rules deliberately to make symbolic points.

But back to Olney.

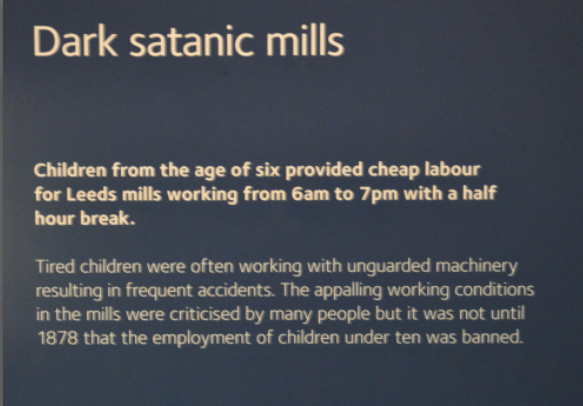

The Newton of the museum’s name is Cowper’s friend and fellow Olney resident, Revd. John Newton (1725-1807). Newton was an abolitionist and hymn-writer, whose most famous lyric is Amazing Grace. A small section of the museum is devoted to his work. There is also a section on the local art of lace making, and another with general local social history collections. Outside are charming gardens, and Cowper’s summer house, which he used as a writing room. Today the visitor can only peer in to the little hut, to prevent us from adding to the graffiti from previous generations of visitors.

The weekend also saw a walk from Olney to nearby Weston Underwood, where another of Cowper’s residences was; that house remains a private home, but the Romantiourist can eat and drink at the Cowper’s Oak pub a few doors down, and visit Cowper’s Alcove, which looks out across fields – another of the poet’s favourite spots.

Cowper’s Alcove

All in all, I had a lovely weekend catching up with a good friend also turned out to be a bit of a busman’s holiday for a Romanticist. But would an academic have it any other way?

You must be logged in to post a comment.