As I mentioned a couple of posts ago, Blake’s ‘To Autumn‘ is a favourite of mine.

Here in America, the season is of course, known as Fall, and glorious it is too – parks resplendent with deep, fiery hues, and skies crisp and clear; here’s a shot taken at Yale’s Cross Campus:

I think Blake would have enjoyed the intensity of Fall colour – lovely as Autumn is, there is a different quality to the colours here.

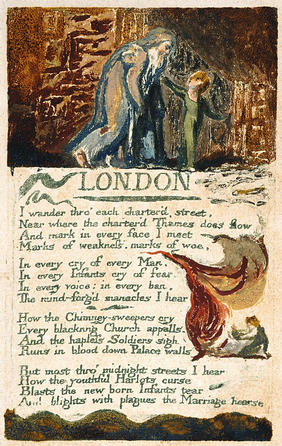

I haven’t come across many trees ‘laden with fruit‘, but I’ve been able to see much fruit of the Blakean kind (i.e. Blake works), both at the Yale Center for British Art where I’m based, and on a long weekend in to New York, where I took in works at the Metropolitan Museum and the Morgan Library.

It’s wonderful to be able to see so many works in person, and I’m looking not only at works that I’ve already done quite a lot of research on, but also at things that I might not otherwise be because they are on hand – both works by Blake himself and by his contemporaries. Whilst I’m here, I’m giving the business of writing up a bit of distance – I’m taking stock of what I’ve written so far and thinking about what I need to write to fill in the gaps, but not writing or editing in earnest. I’m sure when I get back to working on the script more intensely on my return, it will be the richer for spending time with the works themselves.

Beyond the walls of museums, Blake’s habit of cropping up all over the place confronted me twice during my ‘off-duty’ time in New York.

First, I was staying near Columbia University, and therefore had the chance to take in Corpus Christi Church (see picture below), where in a seemingly unlikely combination of life events, Thomas Merton became a Catholic whilst writing his Masters’ dissertation on Blake!

Second, and more well-known, was Lee Lawrie’s ‘Wisdom’ above the entrance to the GE Building at the Rockefeller Center, inspired by Blake’s ‘Ancient of Days.’

Like Paolozzi’s (rather later) fellow compass*-bearing ‘Newton’ at the British Library, this figure towers over a place where large numbers of people pass every day. Both of these monumental sculptures seem to incite the beholder away from the tyrannical, short-sighted worldview which the plates that inspired them symbolise (at least, that’s the standard readings of the figures in both Blake plates, although both have been read in alternative ways, but that’s a matter better saved for discussion elsewhere) to a ‘wiser’ take on the world.

Like Paolozzi’s (rather later) fellow compass*-bearing ‘Newton’ at the British Library, this figure towers over a place where large numbers of people pass every day. Both of these monumental sculptures seem to incite the beholder away from the tyrannical, short-sighted worldview which the plates that inspired them symbolise (at least, that’s the standard readings of the figures in both Blake plates, although both have been read in alternative ways, but that’s a matter better saved for discussion elsewhere) to a ‘wiser’ take on the world.

At more or less the halfway point in my time at the YCBA, the compasses can also serve as a metaphor of pointing two ways: a cause to reflect on my time here thus far, and to look forward to making the most of the fruits available for the remainder of my time.

* Last week during a talk on Blake, I was corrected by a mathematician than Newton and the Ancient of Days are in fact holding dividers, rather than compasses. This is of course a fair point, but ‘compasses’ is rather too ingrained in Blake scholarship for me to give up the habit of using the term.

You must be logged in to post a comment.